Michael Kopp

XANENETLA, PUEBLA, MX

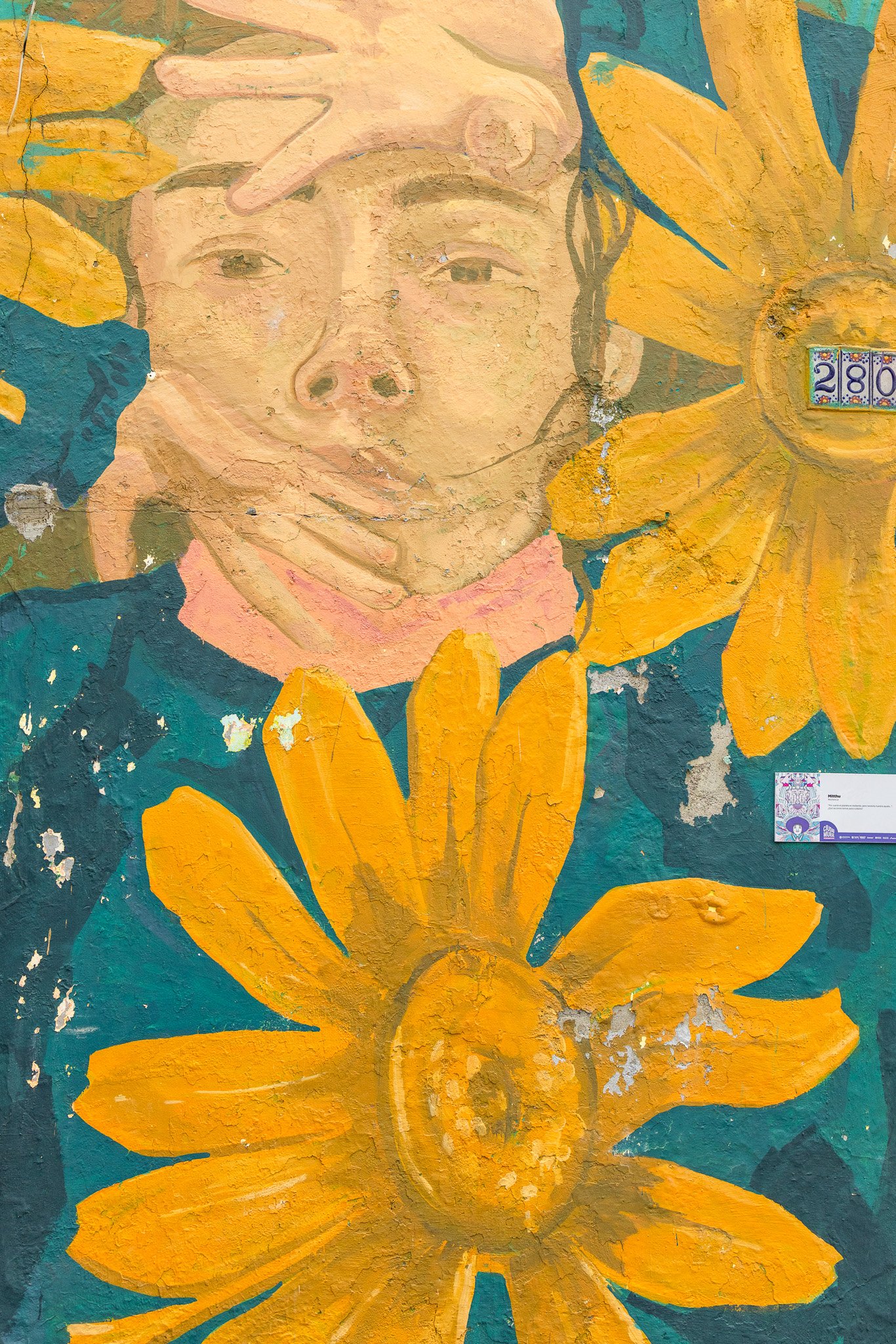

In 2010, Colectivo Tomate launched Puebla Ciudad Mural in the barrio of Xanenetla, a neighborhood historically marginalized within Puebla’s expanding heritage core. Through participatory muralism, the collective transformed domestic façades into a living archive of community memory. Rather than importing an aesthetic, Tomate developed a process rooted in dialogue circles, oral histories, and workshops with residents. The resulting images—of potters, bakers, artisans, and local legends—inscribed the everyday onto the walls of a city increasingly governed by monumental narratives. Over time, more than fifty murals turned the barrio’s streets into a counter-cartography: one that mapped identity and belonging through color, image, and collaboration.

The emergence of Ciudad Mural must be read against the backdrop of Puebla’s inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. Heritage urbanism, as scholars note, often privileges the monumental, the colonial, and the static—stabilizing a curated past that aligns with global tourism markets while marginalizing vernacular knowledge systems. In this context, Tomate’s work offered an insurgent alternative. By privileging lived experience over architectural spectacle, the murals destabilized the authority of heritage branding, producing what might be called a “people’s heritage” on the surfaces of ordinary homes. The project reframed visibility: who and what counts as history, whose labor and stories merit preservation, and how images might serve as tools of social recognition rather than instruments of erasure.

At the same time, Puebla Ciudad Mural illustrates the paradoxes of decolonial public art within neoliberal cities. As the project gained recognition, it risked being absorbed into the very circuits of cultural tourism it sought to critique. The bright facades, initially painted to reflect neighborhood voices, became visual capital in the rebranding of Xanenetla—an area once stigmatized as dangerous now marketed as an open-air gallery. Here, the mural functions as both resistance and commodity, raising difficult questions about co-optation, authorship, and agency. This tension underscores the fragility of decolonial gestures when placed in proximity to UNESCO frameworks, municipal beautification campaigns, and private investment in heritage districts.

Ultimately, Puebla Ciudad Mural should not be understood as a static collection of images but as a social-process artwork: one that foregrounds collaboration, negotiation, and the unstable terrain of cultural representation. Its legacy lies in how it opened the wall as a site of contestation—where community stories confront heritage regimes, and where the politics of visibility are played out in paint. In doing so, the project contributes to broader debates on heritage urbanism and decolonial public art, reminding us that the city’s surfaces are not neutral. They are canvases upon which power is projected, resisted, and reimagined.