In 1987, the historic center of Puebla, Mexico, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List—an act that formalized its cultural value within a global system of recognition premised on preservation, aesthetics, and heritage management. Yet such inscriptions are never neutral; they mark the beginning of a long negotiation between local histories and globalized regimes of visibility. Since the mid-2000s, city and state-led initiatives to “beautify” Puebla’s historic core have intensified. These interventions, while framed as acts of preservation, constitute a visual reordering of the urban fabric—one that privileges a curated colonial aesthetic aligned with heritage tourism and neoliberal development agendas.

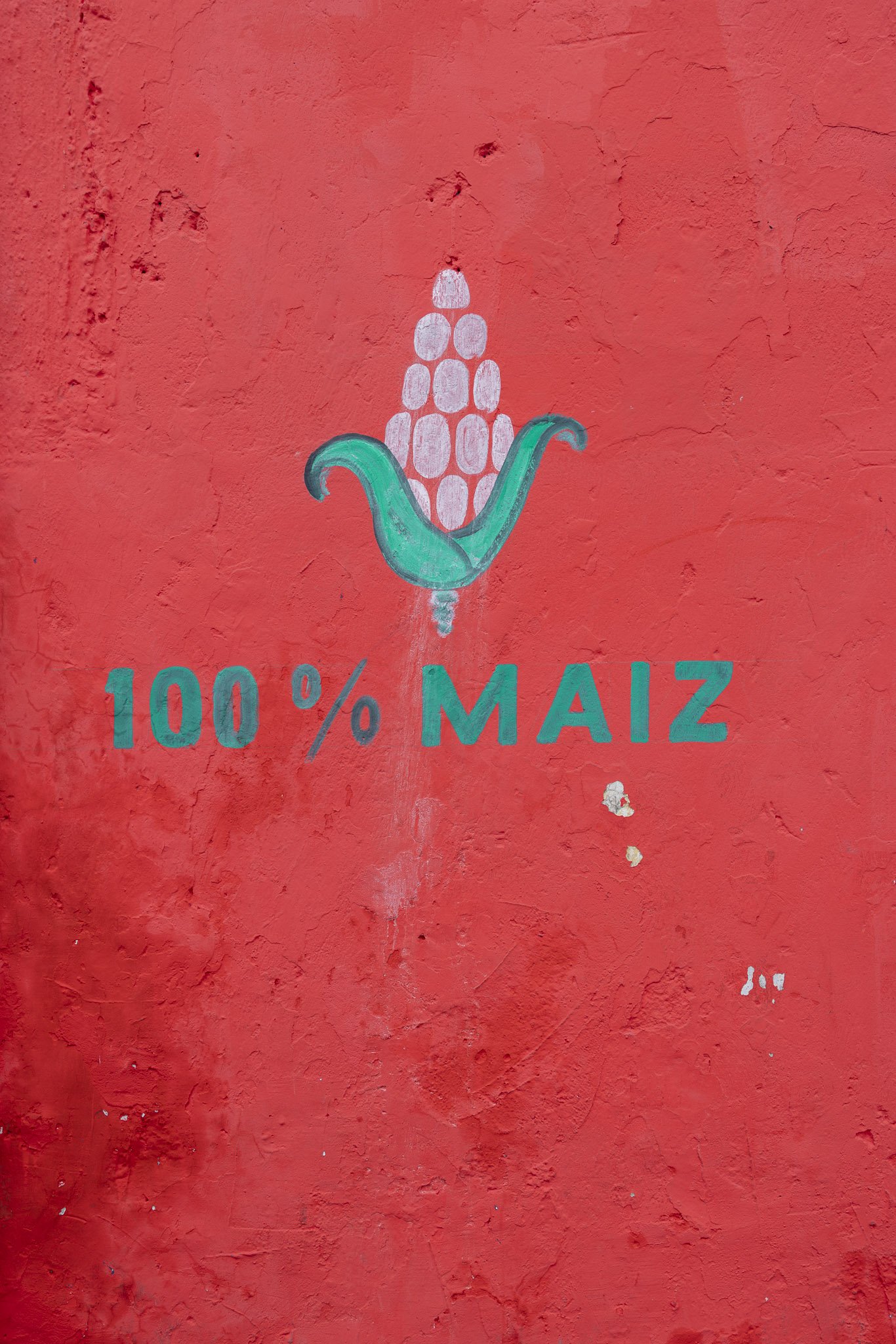

The restoration of facades, repainting of buildings in vibrant hues, and the installation of cobblestone streets signal a shift in how the city’s history is meant to be seen and consumed. Under the guise of “revival,” these efforts reconstruct a sanitized vision of colonial grandeur, displacing the layered and contested histories embedded in the built environment. Such chromatic interventions replace the earthy ochres and terracottas—tones historically derived from the region’s natural pigments—with an idealized palette that performs colonial nostalgia for a global audience. Simultaneously, the presence of talavera tiles, long emblematic of Puebla’s syncretic architectural identity, becomes aestheticized—stripped of their historical contingencies and recast as ornamental markers of cultural authenticity.

The visual history of Puebla is not fixed but has continually shifted in response to political regimes and aesthetic ideologies. From the symbolic whitewashing of facades during neoclassical and Porfirian periods—signaling European modernity—to post-revolutionary returns to vernacular color and material, each phase reveals how architectural surfaces function as canvases for the projection of power. The emergence of heritage conservation movements in the mid-20th century further reframed these surfaces, aligning restoration practices with the demands of a global tourist economy and the cultural capital of UNESCO designation.

This photo-based research engages the visual politics of restoration as a field of contestation. It examines how color, surface, and materiality are mobilized in the ongoing production of heritage-place, asking what is made visible and what is effaced in the pursuit of historic “authenticity.” Rather than documenting the city as a static monument, the work interrogates how architectural interventions mediate historical narratives, circulate ideological values, and reinscribe colonial logics under the banner of preservation.

Question: How does framing (camera, screen, exhibition, i.e.) shape power?

This question sits at the vey intersection of aesthetics, power, and colonial visuality. The subconscious act of framing may actually be where the imperial and the intimate meet. Framing is never neutral. It is a disciplinary gesture, a move that enforces or reinforces the norms, values, and logics of a dominant system. Framing a subtle choreography of control. In visual culture theory (Mirzoeff, Harney & Moten), disciplinary gestures are the micro-technologies (micro-aggressions) of power. They structure visibility: what is seen, how it is seen, and who is authorized to see it. Whether it’s through the viewfinder, the exhibition wall, or a website gallery, framing: Includes and excludes; Directs attention; Normalizes or estranges.

Mirzoeff reminds us that colonial visuality “naturalizes the right to look” only for those already positioned as the seers, not the seen (The Right to Look, 2011). My photographs of Puebla are formal, meticulous, painterly. I am conscious to resist the extractive, touristic gaze, but also revel in surface—facades, textures, chromatic intensity. This raises a tension:

Am I capturing pigment, or is pigment capturing me?

Framing from a distance often echoes colonial architectural photography: the façade-as-evidence. But the intimacy in my photographs disrupts that—the colours bleed, crack, decay. They point not to mastery, but to material histories: What labour, what erasure, what soil made that wall?

Can framing move from composition to entanglement?

There’s an underlying spatial logic at play with this series: verticality, symmetry, control. Many of my frames adopt architectural regularity—grids within grids. This very compositional order echos the colonial order—not by inheritance, but by intent.

These images are intended to seduce the viewer. But what histories made those seductive pigments possible? Cochineal, indigo, lime-wash are all deeply colonial substances, freighted with global circuits of violence and extraction. Each pigment is a material archive—a colour that remembers. Their histories reveal the commodification of the natural world via colonial trade routes; the discipline of vision through aesthetics of power; the racialization of labour, where certain bodies were made to work, produce, and vanish behind the hues they extracted. To photograph pigment is to touch empire, even if obliquely.

Can beauty be a site of responsibility, not just reverence?